Many people suggest that atheists are necessarily barred from holding high political office by virtue of the unpopularity of their world view. Whether that is true or not today, the fact remains that at least one freethinker has achieved high political office in this century.

Many people suggest that atheists are necessarily barred from holding high political office by virtue of the unpopularity of their world view. Whether that is true or not today, the fact remains that at least one freethinker has achieved high political office in this century.On November 7, 1876, Culbert Levy Olson was born in Fillmore, Utah, to a devoutly Mormon mother and a skeptical father. He attended a school run by the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints, but at an early age got into trouble. In a 1961 interview, he described his experiences:

…the children would become so emotional that they would declare they saw angels. Of course I did not see any angels and therefore did not join in the emotionalism stirred up by the preacher. I was called into the principal's office by him. He said that he noticed that I didn't participate in the spirit of the occasion. I told him that I didn't see angels and I didn't believe that the other children did.

Nevertheless, he was admitted to Brigham Young University and graduated at age nineteen in 1895. After graduation, he pursued a career in journalism, finding his way to Washington, D.C. There, he attended a lecture given by Robert G. Ingersoll, and found a tremendous sense of relief and community, realizing that there were others who shared his skepticism about the supernatural.

Thus energized, he entered Columbian Law School, today known as George Washington University School of Law, taking an L.L.M. degree (the equivalent of today’s J.D.) in 1901 with a year’s study at the University of Michigan in his second year. He passed the Utah bar in 1901 and opened a private law practice in Salt Lake City. He married Kate Jeremey in 1905, and described her as a “freethinker” who had some degree of religious faith but was critical of most religious institutions. They had three sons, one of whom followed in his father’s footsteps and entered the practice of law.

By then, Olson had begun a life of political activity (which began by working in 1896 as a campaign volunteer for, of all people, William Jennings Bryan) which increasingly supplanted the practice of law. He was elected to the lower house of the Utah Legislature in 1916, and served two terms until 1920 where he pushed for an end to child labor, support for labor unions, and progressive taxation. A strong proponent of the “reform” movement sweeping the nation at the time, he sponsored and shepherded through the Legislature laws to fight political corruption, establish minimum wages and safe working standards, and to improve the level of social services provided by the state government.

Olson moved to Los Angeles, California in 1920, and was admitted to the California Bar in September of 1921. He was only the 6,335th lawyer in the history of the organized legal profession in California. He became a great supporter of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and worked to implement the principles of FDR’s New Deal in California. Initially a behind-the-scenes operator, he was elected to the California State Senate in 1934 and served one term. He became the head of the Roosevelt wing of the Democratic party, which at that time was split between FDR’s faction, Progressives led by Upton Sinclair, and those who favored compromising with the Republican majority on economic issues, led by the man who would become his Lieutenant Governor, in order to obtain moderate social legislation.

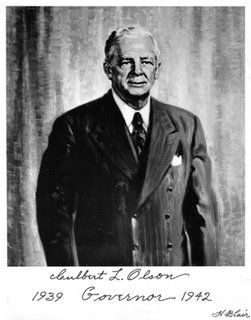

In 1939, Olson ran for Governor and, with FDR’s personal endorsement and an alliance with Sinclair’s progressives, became the first of only four Democrats elected to the California Governor’s office since 1895. His swearing-in was delayed and conducted in private because he refused to include the words “to God” in his oath of office; eventually, a member of the Supreme Court was persuaded to administer the oath in the Capitol building and to accept the words “I affirm” instead.

A friend of Olson in the entertainment industry once said, "If you'd called Central Casting for a governor, Culbert Olson is what they'd have sent you.” Sadly, it seems that Olson’s personality was not as good a fit for the job as his appearance. His problems began with a political mishandling of the then-controversial “Ham and Eggs” initiative. Olson’s campaign carefully ducked this proposal to establish generous state pensions for all retired Californians as a supplement to social security. Once in office, however, Olson sided with economic conservatism over his progressive political instincts and opposed the initiative when it went before the voters, leaving the progressives feeling betrayed.

They should not have; Olson was a dedicated adherent to the generally-progressive social and governmental policies of the Roosevelt Administration and was dedicated to implementing mirror images of those policies at the state level. He took great pains to provide for social welfare programs while attempting to balance a large deficit left over from previous administrations – however, he failed in this regard because his party did not obtain majorities in both houses of the Legislature, and Republicans allied with the fiscally-conservative wing of the Democrats to deny Olson the money necessary to fund his requested social welfare programs.

The most controversial thing Olson did as Governor was to pardon labor activist Tom Mooney, who had been convicted in 1919 of involvement in an attempted bombing of a series of Pacific Gas and Electric Company facilities. Mooney has since been exonerated by further evidence demonstrating that he had been framed, justifying Olson’s pardon. Olson expanded California’s public education system significantly, in particular focusing his efforts on increasing the endowment and number of locations of the University of California. He also recognized, perhaps before any other leader of California, that public utilities required careful regulation and control by the government in order to provide for what were becoming necessities of life such as electricity and natural gas. The Republican-dominated Legislature, however, successfully obstructed Olson’s desires to impose greater regulation, if not public takeover, of these vital entities.

Fulfilling his desire to see an active government in California stimulate economic activity in the midst of the Depression, Olson he established the California Conservation Corps, which hired otherwise unemployed young men to preserve California’s wilderness areas, plant forests and preserve other natural resources. He was an advocate of prison and penal code reform, steering California’s prison system firmly down the road of providing counseling and vocational training to prisoners to encourage them not to commit crimes upon their release, and setting in place reforms to the juvenile justice system, and mental illness treatment provided in conjunction with the criminal justice system, which survive essentially intact today.

World War II came to America in Olson’s administration and Olson largely deferred to military authorities on all significant issues after December 14, 1941 when Olson declared a state of military emergency at President Roosevelt’s request. It is not clear how Olson felt about the military’s decision to relocate Japanese citizens to “holding camps” in the valleys of California’s deserts to the east of the Sierra Nevada mountains; however, Olson did not protest the decision in any fashion. It is also likely Olson became somewhat depressed after the death of his wife after the first year of his administration; he never re-married.

Olson was opposed for his re-election by the Attorney General, Earl Warren. Warren cross-filed and ran for both the Democratic and Republican nominations; he came within 100,000 votes of beating Olson in the Democratic primary because of internecine disagreements between organized labor and progressives within the Democratic party leading to a low turnout. This presaged a solid win by the Republican Warren in 1942. Olson returned to his private law practice in 1943, and while he was still honored in Democratic circles for years afterwards, his political power had clearly vanished. He attended Earl Warren’s inauguration and famously told the future Chief Justice, “If you want to know what Hell is like, just be Governor.” Perhaps out of respect for Olson’s interest in and respect for the University of California system, Governor Warren appointed Olson to the UC Board of Regents, the governing body of that institution.

In 1947, Olson began a campaign of advocating significant changes to California’s constitution, including reform of the Legislature as a unicameral institution, permitting the Governor to appoint Constitutional officers such as the Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, and Secretary of State, and permitting executive deliberation in the process of drafting laws. While his views found some adherents in members of both parties, not enough support has ever been garnered for these ideas to be presented to the voters, and the general structure of California’s Constitution remains one of multiple executives elected independently from one another with a bicameral legislature. He also actively, and successfully, campaigned against the adoption of the phrase “In God We Trust” as California’s official motto.

During his political life, Olson kept his personal atheism quiet and only confided that facet of personal information to trusted colleagues and close family members. Nevertheless, he stated on several occasions that his policies were motivated by “secularism,” which he defined as “…an ethical system founded on natural morality which seeks the development of the physical, moral, and intellectual nature of man to the highest possible point.” He joined the United Secularists of America in 1952 and became its President in 1961. When asked in his later years about his religion by the press, he bluntly replied, “I am an atheist.”

However, he struck a public nerve in May of 1959, when he published an essay entitled “The Problem of Separation of Church and State,” based on an address he had intended to give to the California Commonwealth Club the previous month, but which the Club requested he not give once its subject became known. He presented his view of moral atheism and strict separation of the government from all religious institutions (particularly the Roman Catholic Church) on several television programs in 1959 and 1960, usually writing or speaking on the topic “God is a myth.” He also filed an amicus brief, laced with firey rhetoric, in the California Supreme Court, protesting a lower court’s decision exempting the Catholic Church from paying property taxes because it was a religious institution.

Olson died at the age of eighty-five on April 13, 1962, in a nursing home in Los Angeles and is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California. It is easy to see his term as Governor of California as largely failed because of a lack of tact and misreading of the political landscape; however, it is difficult to see how anyone else could have done much better, given the highly fractious state of politics and the extreme economic, and later military, pressures that California faced during Olson’s term in office. Not all of his political proposals were good, and he was guilty of permitting his late-life criticism of the Roman Catholic Church to cross the line into invective. But, Olson did achieve a very high political office as a freethinker, guided an economically and culturally complex state through some of its hardest times, was a steadfast advocate for bettering the lives of working-class people through civil liberties and economic opportunities, and he laid the foundation for substantial reforms in government and social policy which endure to this day. He remains one of the most ambiguous, and historically controversial, leaders of the Golden State’s history.

Sources:

American Atheists, Inc. biography of Culbert Levy Olson.

California State Library, Biography of Culbert L. Olson.

H. Brett Melendy and Benjamin F. Gilbert, The Governors of California: Peter H. Burnett to Edmund G. Brown (1965).

State Bar of California, profile of Governor Culbert Olson (deceased).

Spartacus Educational, Biography of Culbert L. Olson.

No comments:

Post a Comment