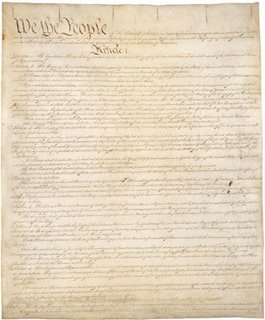

So, he wants to swear his oath of office on the Koran. This has made some people unnecessarily very upset. They ought to calm down and quit trying to force their religion on those who do not share it. The linked article, by the often-priggish Dennis Prager, suggests that the Bible is the foundational document of the United States. Wrong, Dennis. The Constitution is that document. The Constitution requires, in Article VI, as follows:

So, he wants to swear his oath of office on the Koran. This has made some people unnecessarily very upset. They ought to calm down and quit trying to force their religion on those who do not share it. The linked article, by the often-priggish Dennis Prager, suggests that the Bible is the foundational document of the United States. Wrong, Dennis. The Constitution is that document. The Constitution requires, in Article VI, as follows:The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.

I don't see the Judeo-Christian Bible mentioned anywhere in that passage. But wait, there's more. The Constitution requires that there be an oath, but does not specify what that oath is. The oath itself is set by statute, found at 5 U.S.C. § 3331:

I, AB, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.

Now, when it comes right down to it, I have a problem with the last four words of that statute. They seem to directly contradict the Constitutional mandate that "no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States." I suspect that if an elected official or other person required to swear that oath were to challenge it, said official would win both the court case and great political unpopularity, which is why it is still on the books despite its obvious unconstitutionality.

After all, if I were to be elected to Congress by some bizarre circumstance, I would have a bigger political problem on this issue than Ellison does. I could say the whole oath, but I wouldn't really mean the last four words, since I don't believe in God at all. If put in that position, I might very well say them to avoid making a scene, but I would consider them a nullity. I would also probably decline to swear on any book whatsoever, which would give my critics ammunition that Prager does not have against Ellison concerning whether I really meant what I had just said. What book would an atheist swear on? Newton's Principia Mathematica?

After all, if I were to be elected to Congress by some bizarre circumstance, I would have a bigger political problem on this issue than Ellison does. I could say the whole oath, but I wouldn't really mean the last four words, since I don't believe in God at all. If put in that position, I might very well say them to avoid making a scene, but I would consider them a nullity. I would also probably decline to swear on any book whatsoever, which would give my critics ammunition that Prager does not have against Ellison concerning whether I really meant what I had just said. What book would an atheist swear on? Newton's Principia Mathematica? The good people of Minnesota's Fifth District selected this man to represent them in Congress. That cannot now be changed. He's going to serve, and the law requires him to take that oath. But the law does not require him to take that oath on any book whatsoever. That he chooses to consecrate his oath with the book containing what he believes to be the holy word of God indicates his sincerity in that oath.

The good people of Minnesota's Fifth District selected this man to represent them in Congress. That cannot now be changed. He's going to serve, and the law requires him to take that oath. But the law does not require him to take that oath on any book whatsoever. That he chooses to consecrate his oath with the book containing what he believes to be the holy word of God indicates his sincerity in that oath.What's really going on here is that Prager and his ilk are upset that a Muslim is serving in Congress at all. He and his kind used to be upset at the idea that Catholics might serve in the government, on the theory that they would answer to the Pope in Rome rather than the American people. This idea is now considered nothing short of ridiculous. There also used to be an objection to Jews serving in Congress because, well, because they were Jewish. That prejudice is now thought of as a loathsome relic of our ignorant past, and rightfully so.

Yes, there are dangerous Muslims in the world, but there are dangerous Christians and dangerous Jews and dangerous Hindus and dangerous atheists, too. Ellison is entitled to the same presumption of good-faith service and patriotism that any newly-elected Member of Congress gets. We have no more reason to believe that Ellison would do anything against America's best interests than we do any other American citizen, and indeed we should note that he has earned the respect of a majority of members of his district to the point that they are trusting safeguarding the country's interests in him as opposed to his Christian opponent. Singling him out on the basis of his religion is, well, singling him out on the basis of his religion. This is, quite simply, religious discrimination in about the purest form I can imagine. On that subject, I refer the reader back to the foundational document of the United States of America, specifically to its First Amendment.

So let the man swear on his holy book. One holy book is just as good as any other to the Constitution, and it ought to be just as good as any other to the American people. After all, if we're going to insist on controlling what book is sworn on, then why don't we limit the edition of the Bible that's used, too? Then we can argue about whether the approved Congressional Bible should or should not contain the Epistle to the Hebrews or the Book of Wisdom, since not all Christian sects include those books within their canons. That way, we could regress our civilization all the way back to the Thirty Years' War!

I expect that people who know something about Constitutional law would disapprove of Prager's argument. But it's also good to note that there are Christians who really get it on this issue -- for reasons relating to the depth and sincerity of their own religious beliefs.