One of the good things about this blogging phenomenon is that if you play "follow the links" and read a bit, you can come across some things that are quite thought provoking and would never have occurred to you (if only you take the time to engage in thought). I find it's very important to expose myself to new ideas and concepts, even if they are not comfortable and I don't always agree with what is said or like how it makes me feel. Learning and growth occur outside of the comfort zone. Here's an example of that experience which I had recently.

One of the good things about this blogging phenomenon is that if you play "follow the links" and read a bit, you can come across some things that are quite thought provoking and would never have occurred to you (if only you take the time to engage in thought). I find it's very important to expose myself to new ideas and concepts, even if they are not comfortable and I don't always agree with what is said or like how it makes me feel. Learning and growth occur outside of the comfort zone. Here's an example of that experience which I had recently.I got a comment recently from a Reader I who did not recognize. I looked on his blog and found him to be a devout Christian, employed as a math teacher at a high school in Oregon. Seems to be a thoroughly decent guy. A recent post of his was about why he rejects evolution and accepts creation as an explanation for the existence of life. He is intelligent, clearly well-versed on all of the criticisms of evolution, reasonable in his tone, and has a good, fluid, enjoyable writing style. All good things. He is also intellectually honest in advocating "creation" rather than "intelligent design;" he does not attempt to hide the ball about maintaining that God created man, as opposed to, say, time travelers or aliens.

I absolutely disagree with him about that, of course, but that's not quite what I'm writing about today.

My first thought was, "Well, this is a guy who is clearly smart enough to understand evolution but for some reason rejects it. Let's read more and figure out why." I did, and I wound up concluding that regardless of what the scientific evidence might be -- and he finds it lacking on its own merits -- his faith in the truth of Christianity would override it regardless.

Now, my impulsive reaction to that was a desire to point out that he is probably happy to reap the benefits of science in a variety of other ways (medicine, for instance) that are apparently incongruent with the teaching of the Bible. There are some Christians in America who are morally concerned about blood transfusions, for instance, although to be fair to my counterpart, I've no indication that he is among their number and most Christians do not think that transfusions are prohibited.

But then I stopped to think, "Where would that discussion go?" The answer, of course, was "nowhere." Nothing I said, no scientific evidence or pointing out what I perceived to be an inconsistency, no argument I made, would alter his world view. If anything, a confrontation from me would only entrench him in his world view more by virtue of having to erect defenses to my attacks and quite likely having to arm counter-attacks to me. That, after all, was my reaction to his thoughts about skeptics and non-believers. So confrontation didn't seem to be the right response.

The alternatives to confrontation in a setting like this are three in number: acquiescence, withdrawal, or dialogue. Acquiescence would mean agreeing with him, which would be irreconcilably inconsistent with my own world view. Withdrawal would mean nothing. That left dialogue. But after reading more and more of the guy's blog, it seemed that we have little to discuss. His world view is so motivated and dominated by his religious faith that my own perspective on things would seem nearly alien to him. He has been burned by smug, condescending skeptics in the recent past, and is rightly defensive about their name-calling (and clever about turning that name-calling on its head). Trying to take the role of the "reasonable skeptic" would probably not be productive, either; having been recently burned by a rude skeptic, he might reasonably doubt the existence of any other variety of the species or the motives of someone posing as such.

And what would either of us gain from such a discussion? Going back to square one, it's obvious that neither of us are going to change our minds. Nothing he says to me is going to make me suddenly start believing in Jesus Christ as my personal lord and savior; nothing he points out to me will make me start believing in the truth of the Bible as anything other than a compilation of an oral history of legends, archaic rituals, and generalized moral truths. Conversely, nothing I say to him will convince him that the Bible is anything short of God's revealed and direct word to man, that humanity and all the animals and bacteria and all the other life was indeed created through a lengthy process of evolution, or that the best way to look at the world is by way of verifiable and reliable evidence. Indeed, he would likely tell me that the Bible is verifiable, reliable evidence and we could have a long discussion about whether that proposition is true or not.

That then led me to think about these competing world views and how they find themselves expressed in language. Whether the Bible verifiable, reliable evidence depends in part on how you define "verifiable." If your desire is to have the Bible be true, your impulse is to find evidence that "verifies" it. If your desire is to have the Bible be less than literally true, then you will criticize evidence proffered to verify it. So that discussion is ultimately reduced to desire and preference; "faith," if you will, although I eschew using that word when possible. My counterpart in Oregon wants the Bible to be true, so he will view evidence through a lens favoring verification of it; he would say that for some reason I want the Bible to be untrue (not precisely accurate but close enough for discussion purposes), and therefore my lens favors disproof. You find what you are looking for if you go out looking for something.

That then led me to think about these competing world views and how they find themselves expressed in language. Whether the Bible verifiable, reliable evidence depends in part on how you define "verifiable." If your desire is to have the Bible be true, your impulse is to find evidence that "verifies" it. If your desire is to have the Bible be less than literally true, then you will criticize evidence proffered to verify it. So that discussion is ultimately reduced to desire and preference; "faith," if you will, although I eschew using that word when possible. My counterpart in Oregon wants the Bible to be true, so he will view evidence through a lens favoring verification of it; he would say that for some reason I want the Bible to be untrue (not precisely accurate but close enough for discussion purposes), and therefore my lens favors disproof. You find what you are looking for if you go out looking for something.So this, I think, is partially why advocates of creation constantly refer to advocates of evolution as having to have "faith" in evolution. Having been challenged, both sides of this discussion have become defensive and entrenched, and do a lot of sneering at each other and acting smug in the self-assurance of their own correctness and the utter inanity of their opposites' positions.

(Note to self -- being respectful of others' positions requires minimizing one's own smugness.)

Now, I am not a physicist and I do not pretend to understand the intricacies of the theory of gravity; I understand in broad strokes as the force of attraction between two bodies possessing mass. I understand it works on the macro-macro level of stars, planets, and galaxies; I understand it works on the human scale in the form of dropped objects falling to the earth and large ships at anchor in still waters drifting towards each other; I understand it works at the atomic level in the form of electrons orbiting atomic nuclei. I've not personally observed gravity happening at the galactic or atomic levels. I also know that the theory of gravity is still just that, a theory. It has not been ultimately proven and there is substantial disagreement among scientists as to exactly how gravity works and even what gravity really is. But there is no doubt that the phenomenon of gravitation occurs, so there has to be something there.

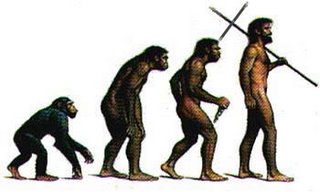

Now, I am not a physicist and I do not pretend to understand the intricacies of the theory of gravity; I understand in broad strokes as the force of attraction between two bodies possessing mass. I understand it works on the macro-macro level of stars, planets, and galaxies; I understand it works on the human scale in the form of dropped objects falling to the earth and large ships at anchor in still waters drifting towards each other; I understand it works at the atomic level in the form of electrons orbiting atomic nuclei. I've not personally observed gravity happening at the galactic or atomic levels. I also know that the theory of gravity is still just that, a theory. It has not been ultimately proven and there is substantial disagreement among scientists as to exactly how gravity works and even what gravity really is. But there is no doubt that the phenomenon of gravitation occurs, so there has to be something there. Evolution is no different. Why do we need antibacterial soaps today when fifteen years ago there were no such things? The answer is that after years of being killed off by the increasing use of regular soap, bacteria have become resistant and now we need stronger stuff to kill them off. Antibiotics have been made stronger in recent years, too, for the same reason. People are taller now than they used to be. Partially this is because of better nutrition and health, to be sure. But even in parts of the world where people seem to be perpetually malnourished and lack any medical care other than first aid, they are still taller than their ancestors on average. So is it also because a majority of humans have developed preferences for tall sexual partners as opposed to short ones and over hundreds of generations height has become an advantage in the cross-generational attempt to propogate one's genes. The fossil record is incomplete and there are many competing theories about how life came to be the way it is today. But something has been going on. And I don't need "faith," "belief," or personal, hands-on knowledge and expertise in the fields of life science, acheaology, public health, or genetics to know that. There are many competing variants of the theory of evolution. But the phenomenon of evolution is something that (to me, at least) appears to be undeniably true and objectively verifiable.

Evolution is no different. Why do we need antibacterial soaps today when fifteen years ago there were no such things? The answer is that after years of being killed off by the increasing use of regular soap, bacteria have become resistant and now we need stronger stuff to kill them off. Antibiotics have been made stronger in recent years, too, for the same reason. People are taller now than they used to be. Partially this is because of better nutrition and health, to be sure. But even in parts of the world where people seem to be perpetually malnourished and lack any medical care other than first aid, they are still taller than their ancestors on average. So is it also because a majority of humans have developed preferences for tall sexual partners as opposed to short ones and over hundreds of generations height has become an advantage in the cross-generational attempt to propogate one's genes. The fossil record is incomplete and there are many competing theories about how life came to be the way it is today. But something has been going on. And I don't need "faith," "belief," or personal, hands-on knowledge and expertise in the fields of life science, acheaology, public health, or genetics to know that. There are many competing variants of the theory of evolution. But the phenomenon of evolution is something that (to me, at least) appears to be undeniably true and objectively verifiable.Gravity, as a broad theoretical concept, is not controversial because its effects are readily observable. This is less true for evolution, however; the process takes generations and large-scale macroevolution takes hundreds of millenia. The phenomenon is easier to observe in organisms with very short life cycles, like bacteria, because in a period of several months or a few years, we can observe hundreds of generations of these creatures reproducing and changing. Evolution also challenges the cherished idea that we as humans are somehow special and different from other things in nature. From there, it is not hard to see its implications that humans lack souls (a soul is not necessary for an animal to survive and reproduce, so why is it necessary for a human). Of course, the fundamental objection religionists make to evolution is its exclusion of the role of a divine creator, as evolution explains the existence of life without reference to such an actor.

This ought to be familiar intellectual ground to anyone who has explored the debate. And I'm sure that my counterpart in Oregon has heard these, or similar, arguments before. And I'm also sure that he has rebuttals to them -- I read some of them already. So that leaves me with a conundrum.

1. We both have arguments in support of our own positions which we find completely intellecutally satisfying to ourselves and to others who already agree with us.

2. We both have arguments attacking one anothers' positions which we and those who already agree with us find intellectually devastating.

3. We both think the others' arguments are fundamentally flawed and weak, for a wide variety of reasons.

4. Anything that one says to the other will not only fail to convince, but rather produce greater entrenchment in the initial position.

5. We both know points 1-4 at the onset of the discussion.

So what's the point of having the discussion at all? What do we really have to say to each other? What value can come out of a dialogue other than frustration? There is some entertainment value to having an argument, I suppose. But down that road lies the intellectual abyss that was CNN's Crossfire -- talking heads shouting at each other about politics presented as a form of entertainment instead of smart people intelligently debating an issue of the day. And particularly with this issue, it seems that two people can look at the same body of evidence and see entirely different things. It also gets difficult, at that point, to avoid giving the impression of smug disrespect for the other, even if that attitude was not intended.

So what's the point of having the discussion at all? What do we really have to say to each other? What value can come out of a dialogue other than frustration? There is some entertainment value to having an argument, I suppose. But down that road lies the intellectual abyss that was CNN's Crossfire -- talking heads shouting at each other about politics presented as a form of entertainment instead of smart people intelligently debating an issue of the day. And particularly with this issue, it seems that two people can look at the same body of evidence and see entirely different things. It also gets difficult, at that point, to avoid giving the impression of smug disrespect for the other, even if that attitude was not intended.It's easy to dismiss the side of such an issue with which you disagree as misinformed or erroneous doctrine. Down that road lies fanaticism. It's difficult to remember that people tend to do what they do because it seems like the right decision. People subscribe to the religions they do because they think it is morally right to do so; they act on their faith because they think it is morally right to do so. That's even the case when faith motivates people to violence like we see being played out today in the Middle East. We would like to say that such peoples' faith has been perverted and perhaps that is true sometimes. But it is nevertheless the case that they do what they do because they think it is morally right to do so. And if someone opposes them, what is the obvious conclusion to draw about someone who opposes something known to be morally right?

In the law, we deal with irreconcilable views of things all the time. We deal with it by having a verdict -- you know that in every lawsuit, at least one of the litigants is wrong; at least one of the litigants is going to lose. Hopefully, the fear of losing motivates people to compromise, and if that does not work then the high transaction costs of prosecuting your point of view often does. But if fear and expense are not sufficient to induce compromise, you know that the sword will eventually fall.

There are other dispute resolution mechanisms in social contexts. One of them is democracy. Another is violence. A third is dialogue. But the thing about dialogue is that it has a very low transaction cost, and it induces no fear. Unlike litigation, or democracy, or violence, there is no incentive that is part of the dialogue that encourages the parties to resolve their disputes. All dialogue does is provide a way for people who wanted to resolve their dispute to begin with to have a forum in which to do so. But when the dispute takes on moral weight, the parties lose their desire to compromise or resolve their disputes, or ultimately to even tolerate opposing points of view.

What I'm wondering today is whether dialogue on issues like this is even possible. It is clear, for instance, that dialogue on other issues has become impossible. Take abortion -- on that issue, there has been almost complete polarization and there is very little ability to compromise on either side of the issue. One is either pro-choice or pro-life; there is no middle ground, there is no room for debate because the premises underlying both sides of the debate are so radically different from one another -- and more importantly, so heavily-invested in the moral correctness of their position, and the demonization of the other, that dialogue, debate, and discussion are replaced with invective, name-calling, and demonization. That evolution is a simialrly polarizing subject is hardly a new phenomenon; it has caused sharp cries of "foul" from the devoutly religious since before Darwin sailed on the HMS Beagle to the Galapagos Islands.

What I'm wondering today is whether dialogue on issues like this is even possible. It is clear, for instance, that dialogue on other issues has become impossible. Take abortion -- on that issue, there has been almost complete polarization and there is very little ability to compromise on either side of the issue. One is either pro-choice or pro-life; there is no middle ground, there is no room for debate because the premises underlying both sides of the debate are so radically different from one another -- and more importantly, so heavily-invested in the moral correctness of their position, and the demonization of the other, that dialogue, debate, and discussion are replaced with invective, name-calling, and demonization. That evolution is a simialrly polarizing subject is hardly a new phenomenon; it has caused sharp cries of "foul" from the devoutly religious since before Darwin sailed on the HMS Beagle to the Galapagos Islands.But what I'm wondering isn't really about abortion, or evolution. What I'm wondering is whether differences of opinion on matters of moral significance are really subject to a social dialogue at all. Like I said at the start of this essay, learning and growth occur outside of one's own personal comfort zone, and disputes like this are uncomfortable. Have we as a people reached a point where willful ignorance has become the ascendant ethic; where winning is more important than being right; where we reject the idea that we can grow and learn from each other?

3 comments:

One option I see is "agree to disagree." In this instance you could both agree to not bother discussing morally charged subjects as neither of you will ever change your stance.

That does not mean you could never discuss other topics with this person. Clearly both parties involved in this example are intelligent and have many wonderful insights about the world at large. You still have plenty to learn from one another. To completely write off or ignore someone who does not share your views will not promote growth, but the opposite.

Well, I made a comment on a different issue (same-sex marriage) on this man's blog just moments ago. I suppose that means I am doing exactly what you suggest.

I think your post makes one thing certain. You and your type are what drags our society down into the moral abyss. Not as one who disagrees with me on topics such as evolution and gay marriage but as a lawyer. As a math teacher I would never have the patience to write a post 1/3 the length of yours. The length of that post could only be achieved by a lawyer. Of course, I am only giving you a hard time (just in case people reading this think I am serious). Apart from the length, it was a worthwhile read and had some good insights. I agree with you that a back and forth debate would not change either of our minds though it is nice to hear from someone who disagrees with me and keeps the conversation clear of insults and defensive counter-attacks. I try to do the same and look forward to reading more of your posts and hope you continue to do the same with mine. Thanks for comments.

Your Oregon Counterpart.

Post a Comment